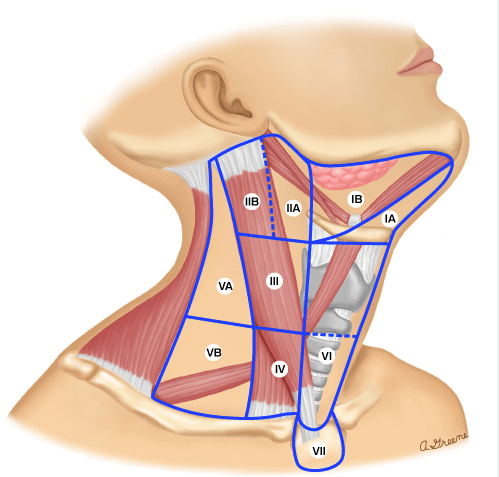

- The basis and need for elective nodal treatment in head and neck cancer:

- Have been based largely on surgical series evaluating pathologic nodal involvement found on elective neck dissection in patients with clinically negative necks

- In a consecutive series of 1,081 head and neck cancer patients undergoing radical neck dissection:

- The incidence of pathologic node involvement:

- Was 33% among those undergoing elective neck surgery

- The pathologic findings identified the nodal stations at risk by tumor site:

- To establish the rationale for selective neck dissection (SND) as the elective surgical procedure

- The incidence of pathologic node involvement:

- Several reports have summarized the risk for metastases and nodal stations at risk

- Some general observations from such data can be made:

- Regarding larynx cancers:

- Candela reported the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) experience in determining the patterns of cervical nodal metastases in 247 larynx cancer patients undergoing radical neck dissections:

- Seventy-eight underwent elective radical neck dissection whereas 118 underwent immediate radical dissection for clinically node-positive disease

- The majority of patients (n = 189) were supraglottic larynx and 58 were glottic

- Pathologic nodal involvement:

- Was found in 37% undergoing elective neck dissection

- It is noted that cervical nodes spread in a similar fashion whether the patients are clinically node negative or positive:

- With predominant involvement of:

- Level II and III jugular nodes

- With predominant involvement of:

- In clinically node-negative patients:

- The incidence of involvement of level I and V:

- Is less than 5% with less than 10% involvement of level IV

- The incidence of involvement of level I and V:

- In node-positive patients:

- The incidence of level IV node increases from 15% to 31% with greater involvement of levels II and III

- In clinically node-positive patients:

- Very rarely did patients present with isolated level I nodal metastases without involvement of the jugular nodes

- Candela reported the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) experience in determining the patterns of cervical nodal metastases in 247 larynx cancer patients undergoing radical neck dissections:

- Regarding larynx cancers:

- Shah and Candela reported that among oropharynx or hypopharynx cancers:

- Treated with elective radical neck dissection:

- Occult metastases are found in 26%

- Level I and V were involved in only 1.4%:

- Always in association with nodal disease at level II to IV

- No skip metastases were reported

- Among oropharynx patients:

- Levels II to IV were predominantly involved

- Among hypopharynx lesions:

- The primary levels involved were levels II and III

- In patients clinically node positive undergoing therapeutic neck dissection:

- The incidence of level I and V involvement increased to about 10% to 15%:

- However, levels II to IV were predominantly involved

- Level V involvement:

- Only occurred in association with nodal involvement at levels II to IV

- Whereas the incidence isolated level I involvement without levels II to IV involvement (“skip metastasis”):

- Occurred in 0.4%:

- Thus, based on these studies, elective treatment of the neck in oropharynx or hypopharynx can be directed at levels II to IV

- Occurred in 0.4%:

- The incidence of level I and V involvement increased to about 10% to 15%:

- Treated with elective radical neck dissection:

- Among oral cavity patients:

- The incidence of nodal disease was 34% on elective evaluation

- The majority of metastatic nodes involved:

- Levels I to III:

- With only 1.5% incidence of skip metastasis to level IV

- Levels I to III:

- Level V involvement:

- Is found in only 0.5% with occult disease simultaneously involving other levels

- Among those undergoing therapeutic neck dissections:

- The incidence of level IV involvement increased to 20%

- Level V was 4% always restricted to lower gum or floor of mouth primary sites

- The need for elective treatment not only relates to the estimated probability of nodal involvement and usually is implemented when the risk is 20% or greater but also relates to the morbidity of such treatment as well as the adequacy of coverage

![warthin-tumor-parotid-[1-pa003-1]](https://arrangoizmd.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/warthin-tumor-parotid-1-pa003-1.jpeg)