Radioactive Iodine (RAI) for Thyroid Cancer – Who Really Needs It in 2026?

Radioactive iodine (RAI, I-131) is used after thyroid surgery in selected cases of differentiated thyroid cancer (papillary and follicular). Its goals are:

to destroy tiny remnants of thyroid tissue (“remnant ablation”), to reduce the risk of recurrence (“adjuvant therapy”), or to treat known persistent or metastatic disease.

Over the last decade, we’ve learned that many low-risk patients do just as well without RAI, so we now use it much more selectively.

1. When is RAI usually recommended?

Most societies (ATA, ETA, NCCN, SNMMI/EANM) and recent data support using RAI mainly for intermediate- and high-risk disease.

RAI is typically recommended when:

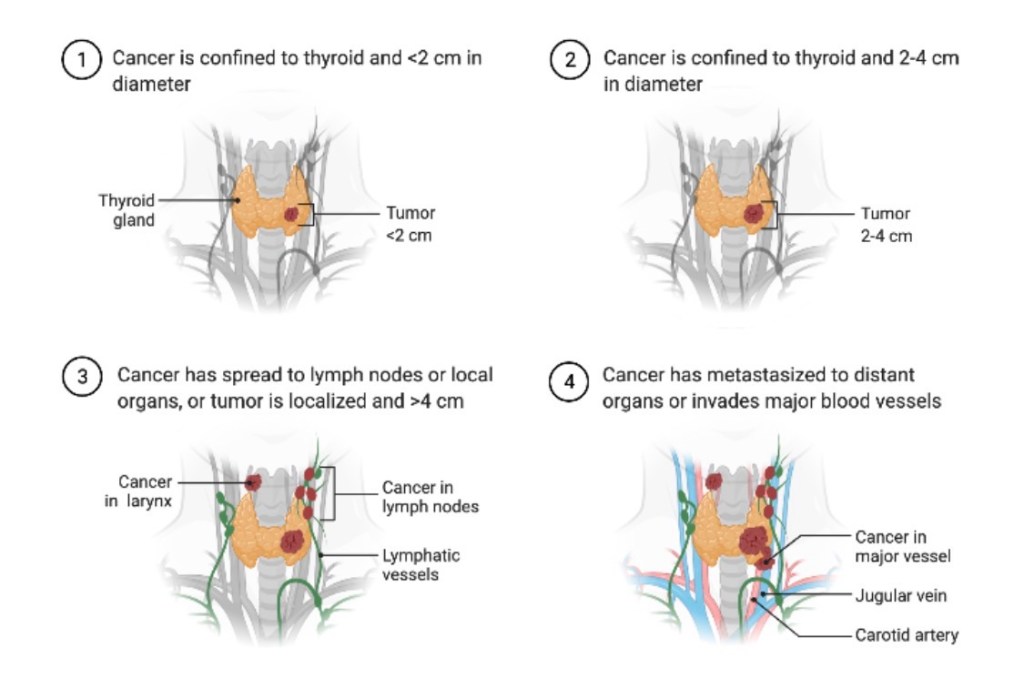

High-risk disease (ATA high risk) Gross extrathyroidal extension Large primary tumors Extensive nodal disease (multiple or large metastatic nodes) Distant metastases (lung, bone, etc.) Selected intermediate-risk disease Microscopic extrathyroidal extension Multiple involved lymph nodes Aggressive histologic variants Here, RAI is considered and individualized based on age, tumor biology, thyroglobulin, and patient preferences. Persistent or recurrent disease Elevated or rising thyroglobulin after surgery Iodine-avid metastatic disease on imaging

2. When is RAI often not needed?

For many patients with true low-risk differentiated thyroid cancer, excellent outcomes can be achieved with surgery and careful follow-up without RAI.

The ESTIMABL2 randomized trial showed that in low-risk patients (small, node-negative tumors), follow-up without RAI was non-inferior to routine RAI at 5 years, with no loss of oncologic opportunity. The 2015 ATA guidelines and subsequent analyses recommend that RAI is not routinely used in ATA low-risk patients, particularly for tumors ≤4 cm without worrisome features.

For many patients, this means less treatment, fewer side effects, and the same excellent prognosis.

3. Common short-term side effects

Most side effects are mild and temporary:

Neck discomfort or swelling Nausea, metallic taste, or loss of taste Dry mouth or thick saliva Swollen, tender salivary glands (parotid/submandibular sialadenitis) Fatigue for days to weeks Temporary changes in blood counts (mild bone-marrow suppression)

Some patients also report:

Dry eyes, tearing problems, or a “gritty” sensation Nasal dryness and crusting

4. Less common or long-term risks

These are less frequent but important to discuss before treatment:

Chronic salivary gland dysfunction Persistent dry mouth (xerostomia) Difficulty with chewing/swallowing dry foods Increased dental caries and oral infections Lacrimal (tear duct) problems Nasolacrimal duct obstruction → watery or irritated eyes Sometimes requires ophthalmology intervention Fertility and pregnancy Transient effects on sperm parameters and ovarian reserve have been described at higher cumulative doses, so we usually recommend avoiding pregnancy for 6–12 months after RAI and consider sperm banking in selected young men likely to need repeated high-dose treatments. Second primary malignancies (very rare) Large observational studies suggest a small increase in risk of secondary malignancies (e.g., leukemia, salivary gland tumors) at higher cumulative doses, which reinforces the move toward lower doses and more selective use.

5. How we minimize and manage side effects

a) Use the lowest effective dose

Trials such as HiLo and related studies have shown that low-dose (≈30 mCi) RAI with recombinant TSH is as effective as higher doses for remnant ablation in low-risk patients, with fewer side effects.

b) Protect salivary glands

Aggressive hydration for several days after therapy Frequent chewing (sugar-free gum) and sour candies starting after the first 24 hours, as guided by the treating team, to stimulate saliva flow Good oral and dental hygiene, with dental follow-up for patients receiving higher doses In selected patients with significant chronic symptoms, sialogogues (pilocarpine, cevimeline) and targeted ENT/salivary management may help

c) Protect eyes and tear ducts

Artificial tears and ocular lubricants from the early post-treatment period Early evaluation by ophthalmology if tearing, pain, or recurrent eye infections develop In selected complex cases, interventional approaches to the nasolacrimal duct can be considered.

d) Monitor blood counts and overall health

Baseline and follow-up blood counts in patients receiving moderate/high doses Correct nutritional deficiencies and manage anemia or other cytopenias if they occur

e) Clear radiation-safety instructions

Temporary restrictions on close contact with children and pregnant women, sleeping in the same bed, and travel, adapted to the administered dose and national regulations.

6. Take-home messages for patients

Not everyone with thyroid cancer needs RAI. Many low-risk patients do very well with surgery and surveillance alone. When indicated, RAI can reduce recurrence and treat iodine-avid metastatic disease, particularly in higher-risk patients. Most side effects are short-term and manageable; long-term complications are less common and are more likely with higher cumulative doses. Careful risk stratification, dose selection, and prevention strategies (hydration, salivary and ocular care, blood count monitoring) are key to minimizing toxicity. Decisions about RAI should be personalized, ideally made in a multidisciplinary team with a thyroid surgeon, endocrinologist, and nuclear medicine specialist.

Suggested references (for the post footer)

Haugen BR, et al. 2015 American Thyroid Association Management Guidelines for Adult Patients with Thyroid Nodules and Differentiated Thyroid Cancer. Thyroid. 2016. Pacini F, et al. What are the indications for post-surgical radioiodine therapy in differentiated thyroid cancer? Eur Thyroid J. 2022. Leboulleux S, et al. Thyroidectomy without radioiodine in patients with low-risk thyroid cancer (ESTIMABL2, 5-year follow-up). Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2025. Mallick U, et al. Ablation with low-dose radioiodine and thyrotropin alfa. N Engl J Med. 2012. (HiLo trial) Nguyen NC, et al. Radioactive Iodine Therapy in Differentiated Thyroid Cancer: An Update on Dose Recommendations and Risk of Secondary Primary Malignancies. Semin Nucl Med. 2024. Orosco RK, et al. Radioactive iodine in differentiated thyroid cancer. Head Neck. 2019. Jeong SY, et al. Salivary gland function 5 years after radioactive iodine ablation. J Nucl Med. 2013. Solans R, et al. Salivary and lacrimal gland dysfunction after radioiodine therapy. J Nucl Med. 2001. Baudin C, et al. Dysfunction of the salivary and lacrimal glands after radioiodine therapy: START study. Thyroid. 2023. Rahmanipour E, et al. Eye-related adverse events after I-131 radioiodine therapy: systematic review. Endocr Pract. 2024. Berta DM, et al. Effect of radioactive iodine therapy on hematological parameters: systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Endocrinol. 2025.

Author:

Rodrigo Arrangoiz, MD

Surgical Oncologist & Thyroid Surgeon

Mount Sinai Medical Center – Miami, FL