- Primary treatment with concurrent chemotherapy and radiation therapy has been accepted widely as a standard of care:

- Since the publication of the Meta-Analysis of Chemotherapy on Head and Neck Cancer in 2000:

- This meta-analysis was later updated in 2009:

- Involving an analysis of 50 trials:

- That showed an absolute survival benefit of 6.5% at 5 years:

- Associated with administering chemotherapy concurrently with radiation

- That showed an absolute survival benefit of 6.5% at 5 years:

- Involving an analysis of 50 trials:

- This meta-analysis was later updated in 2009:

- Since the publication of the Meta-Analysis of Chemotherapy on Head and Neck Cancer in 2000:

- Bolus cisplatin (100 mg/m2 on days 1, 22, and 43) concurrent with radiation therapy:

- Has been extensively studied:

- May be considered the standard to which other chemotherapy regimens are compared in clinical research

- The intergroup trial conducted by Adelstein and colleagues was influential in establishing this regimen (bolus cisplatin 100 mg/m2 on days 1, 22, 43 concurrent with radiation therapy) as a standard of care (Figure)

- Has been extensively studied:

- In a three-arm randomized phase III trial of 295 patients with locally advanced (unresectable) stage M0 head and neck squamous cell carcinoma:

- The treatment groups were radiation therapy alone (70 Gy) versus identical radiation plus concurrent cisplatin (100 mg / m2 administered intravenously on days 1, 22, and 43) versus a split course of radiation with cisplatin plus 5-FU

- With a median follow up of 41 months:

- The concurrent cisplatin / radiation arm had a significant advantage in:

- Survival at 3 years compared with radiation alone:

- 37% versus 23%, p = .014

- Survival at 3 years compared with radiation alone:

- Survival in the split-course concurrent arm:

- 27% was not significantly better than that in the radiation arm

- This improved efficacy comes at the cost of an increased incidence of acute toxicities, including:

- Mucositis and nausea / vomiting:

- Four toxic deaths occurred among 95 patients enrolled in the cisplatin chemoradiation arm

- Mucositis and nausea / vomiting:

- The concurrent cisplatin / radiation arm had a significant advantage in:

- The intergroup Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG 91–11) trial for advanced larynx cancer (Figure):

- Established concurrent bolus cisplatin with radiation as a standard of care

- The study was open to patients with:

- Squamous cell carcinoma of the glottic or supraglottic larynx

- Patients with T1 disease or large-volume T4 disease:

- Were excluded

- Median follow-up of the study was:

- 3.8 years

- Patients were randomly assigned to one of three larynx preservation strategies:

- Induction cisplatin plus 5-FU followed by radiotherapy:

- Patients with less then partial response after 2 cycles of PF:

- Underwent laryngectomy followed by adjuvant radiotherapy

- Patients with less then partial response after 2 cycles of PF:

- Radiotherapy with concurrent cisplatin

- Radiotherapy alone

- Induction cisplatin plus 5-FU followed by radiotherapy:

- The dose of radiotherapy to the primary tumor and clinically positive nodes was:

- 70 Gy in all treatment groups

- Severe or life-threatening mucositis in the radiation field:

- Was almost twice as common in the concurrent treatment group compared with either the radiotherapy alone group or the sequential treatment group

- The primary endpoint of the study was:

- Preservation of the larynx

- The rate of laryngeal preservation was:

- 84% for patients receiving radiotherapy with concurrent cisplatin

- 72% for patients receiving induction chemotherapy followed by radiation

- 67% for patients receiving radiation therapy alone

- Distant metastases were reduced in patients who received either:

- Concurrent chemoradiotherapy or induction chemotherapy followed by radiotherapy:

- Compared with patients who received radiotherapy alone

- Concurrent chemoradiotherapy or induction chemotherapy followed by radiotherapy:

- Overall survival was not significantly different among the three treatment groups:

- The lack of an overall survival difference between the three groups:

- May be due to the contribution of salvage laryngectomy in all groups:

- As well as a 2% increase in the incidence of death that may have been related to treatment in the concurrent chemoradiotherapy group compared with the other two treatment groups

- May be due to the contribution of salvage laryngectomy in all groups:

- The lack of an overall survival difference between the three groups:

- It is important to recognize that the primary endpoint of the study was larynx preservation:

- Not overall survival

- The current standard of care for larynx preservation:

- Remains concurrent high-dose cisplatin and radiation for patients who fit the eligibility criteria that were used in RTOG 91–11

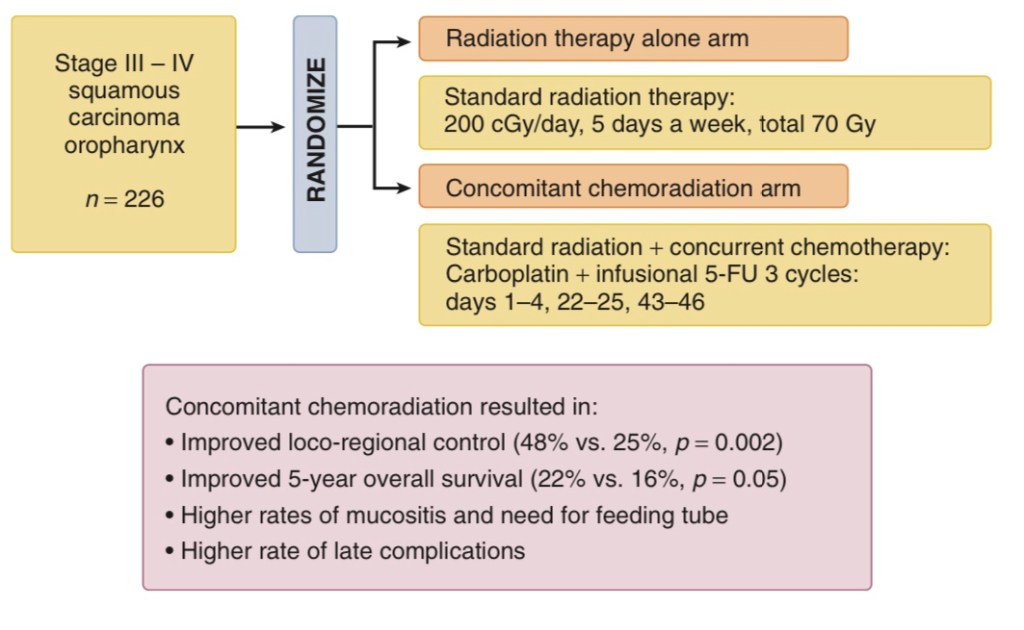

- The Groupe d’Oncologie Radiotherapie Tete et Cou trial:

- Is important because it evaluated the concomitant approach in patients with:

- Oropharynx cancer only (Figure)

- A total of 226 patients were randomly assigned to either radiation therapy alone (70 Gy) or radiation therapy (70 Gy) with concurrent carboplatin and infusion 5-FU

- Significant benefits in 5-year:

- Overall survival:

- 22% versus 16%, p = .05

- Locoregional control:

- 48% versus 25%, p = .002

- Were noted in the combined treatment arm

- 48% versus 25%, p = .002

- Complete responses were observed in a significant number of patients:

- Thus avoiding the sequelae and short-term morbidity of surgical resection

- Overall survival:

- Is important because it evaluated the concomitant approach in patients with:

et al. Randomized trial of radiation therapy versus concomitant chemotherapy and radiation therapy for advanced-stage oropharynx carcinoma. J Natl Cancer Inst 1999;91:2081–2086 and Denis F, Garaud P, Bardet E, et al. Final results of the 94-01 French Head and Neck Oncology and Radiotherapy Group randomized trial comparing radiotherapy alone with concomitant radiochemotherapy in advanced-stage oropharynx carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 2004;22:69–76.)

- Phase II trials also support the feasibility of administering other chemotherapy regimens concurrently with radiation therapy for patients with locoregionally advanced head and neck cancer, including but not limited to:

- Cisplatin plus paclitaxel

- Cisplatin plus infusional 5-FU

- 5-FU plus hydroxyurea

- Carboplatin plus paclitaxel

- Paclitaxel, 5-FU, and hydroxyurea

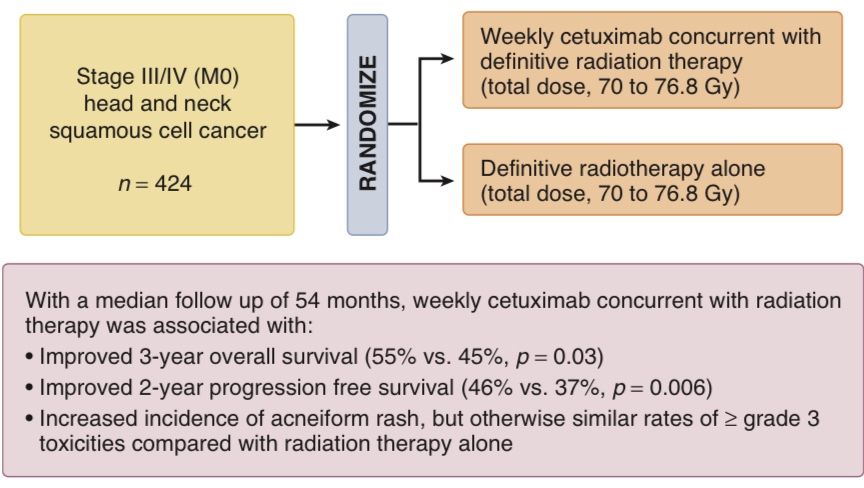

- The role for cetuximab in combined modality therapy:

- Was established when Bonner and colleagues randomly assigned 424 patients with locoregional advanced head and neck squamous cell cancer to treatment with:

- Radiation therapy alone or radiation therapy with concurrent weekly cetuximab (Figure)

- Was established when Bonner and colleagues randomly assigned 424 patients with locoregional advanced head and neck squamous cell cancer to treatment with:

- Investigators were required to choose between one of three radiotherapy fractionation regimens:

- With a total dose of 70 to 76.8 Gy

- With a median follow-up of 54 months:

- The combined treatment group had significantly improved:

- 3-year locoregional control:

- 47% versus 34%, p < .01

- 3-year overall survival:

- 55% versus 45%, p = .05

- Compared with the group that received radiation therapy alone

- 55% versus 45%, p = .05

- 3-year locoregional control:

- The combined treatment group had significantly improved:

- Cetuximab was associated with an increased risk of:

- Severe acneiform rash (17%) and severe infusion reaction (3%)

- While cetuximab and radiotherapy is a valid treatment option for this patient population:

- Retrospective studies have suggested that cetuximab may be associated with inferior outcomes compared with cisplatin and carboplatin plus infusional 5-FU:

- Riaz et al., 2016; Shapiro et al., 2014

- Retrospective studies have suggested that cetuximab may be associated with inferior outcomes compared with cisplatin and carboplatin plus infusional 5-FU:

- Recently, two randomized phase III trials were conducted to test if cetuximab may serve as a non-inferior and less toxic alternative to cisplatin in combination with radiation for patients with localized HPV-positive oropharyngeal carcinomas (which possess superior clinical outcomes with cisplatin chemoradiation compared to HPV-negative patients; Ang et al., 2010):

- The De-ESCALaTE HPV trial:

- Restricted enrollment to low risk HPV-positive patients (less than 10 pack-year smoking history):

- They observed a significantly superior 2-year overall survival with cisplatin over cetuximab:

- 97.5% versus 89.4%; hazard ratio 5.0 [95% CI 1.7-14.7]; p=0.001; Mehanna et al., 2018

- They observed a significantly superior 2-year overall survival with cisplatin over cetuximab:

- Restricted enrollment to low risk HPV-positive patients (less than 10 pack-year smoking history):

- RTOG 1016 also demonstrated that among HPV-positive oropharyngeal cancer patients:

- Cetuximab failed to meet the pre-specified non-inferiority criteria for overall survival compared to cisplatin:

- Estimated 5-year overall survival of 77.9% [95% CI 73.4-82.5] with cetuximab versus 84.6% [95% CI 80.6-88.6] with cisplatin; Gillison et al., 2018

- Cetuximab failed to meet the pre-specified non-inferiority criteria for overall survival compared to cisplatin:

- Both trials also demonstrated that toxicity rates were not significantly lower with cetuximab

- Taken together, these prospective data argue strongly for prioritizing the use of cisplatin in these clinical settings and reserving the use of cetuximab with radiation in those who are not cisplatin-candidate

- The De-ESCALaTE HPV trial:

#Arrangoiz #CancerSurgeon #HeadandNeckSurgeon #SurgicalOncologist #LarynxCancer #MountSinaiMedicalCenter #MSMC #Miami #Mexico